East of Where East Begins

My eyelids rose to unveil a room black as dark mode and void of detail.

The blankets clung to my shoulders, as the unforgiving summer of the Midwest made 5 a.m. wake-up calls a sweat-inducing ritual. Thin sheets still feel like an oven in August. The iPhone alarm went off shortly after the hotel desk issued an automated wake-up call to the room, from one of those rotary landlines that had a massive cord hanging off of it, like the dispatch center in John Wick films. Silence died as the air between my runner’s knees popped, and the frame of my body stood shadowless in front of the walls to the shower. Sauntering over to the sliding doors, my southpaw made a few swipes to shut the backup alarms off, clear Teams notifications, and give my inkless right arm the opportunity to multitask by starting the shower and leaving its handle over the blue line.

1,500 miles of driving to the shores of the Outer Banks from Missouri.

That’s what waited for me after this cold rinse and a quick walk to the best coffee shop downtown.

By the time Friday realized I was awake and tried to get the sun fully above the horizon, my ass had already tipped the barista, sauntered a few loops around downtown, and made it onto the road. People regularly ask why the fuck anyone would do this sort of drive willingly, but I love it. Planes are faster. Terminals charge six bucks for bottled water and ten for the ones with blue check marks. The stewardesses are always pretty. Everyone fucks with the free pretzels, too. But there are days when you don’t want that efficiency—you want control. You want the wheel in your hand, the front seat to carry your camera bag, and no one telling you when to fasten a belt or how much legroom your life gets.

Glancing over, my Leica sat cheerfully on top of the waxed canvas pack. No lens cap was attached, and its three batteries were fully charged. Thousands of moments could happen, and each one would have a place in the archive from this escapade across all-American terrain. It was the perfect co-pilot. Didn’t need to pick the music, just be ready for anything that could cross our paths.

This pairing worked well because the 74-inch-tall collection of calcium and tissue that I am wanted asphalt and billboards. Vivid colors and the chance to set a shutter speed higher than 1/2000th of a second. My tortoiseshell Gucci glasses clamped down on the bridge of my nose, guarding the two optical picture-producing brown planets that my genes gave me while Bon Iver sobbed out the speakers and cold brew sweated in the cup holder. A few turns later I was squarely in the fiery wake of red and orange clouds. Major Tom didn’t need to be sung by a brunette this time—the RPMs climbed high enough on their own without any motivational singing. And the gentle click of the shutter opening prompted me to start snapping away. I was untouchable.

Hours blurred. The fence around my mind came down. Freedom and light fused into something holy. Church made of steel and rubber with BF Goodrich for cornerstones. And in the pulpit of that lane, I caught myself smirking, connecting ideas, and dreaming without sleep. That paradox again—running away from it all, and somehow closer to it at the same time. This happens a lot, and continued as all of my trips do, only ever pulling the needle off the record when reality, gas stops, drive-thru quesadillas, and taking a piss demanded precedence. The urge to get more tattoos also surfaced around midday, when the sun bathed the back of my neck and the flash of my camera, swinging on my shoulder against a white tee and jeans, garnered a look or two. Could’ve been the resting bitch face, but in the Midwest anyone walking around with a camera gets asked what they’re writing for the Times. Tattoo additions aren’t an urge to get ink-for-ink’s sake though. It’s that itch to carve permanence while everything else flies past at eighty. Scribbled scars pointed like a compass to previous pages in the book. Driving makes me want that. The permanence of it. A way to trick my own body into remembering what my head doesn’t see anymore.

Historians will look back and tell kids in classrooms that Chipotle bags were inspired by our tiny tattoo collections—I’m fucking certain of it.

When the fuel pump receipt was printed, my American Express raised its eyebrows. Whoever decided after two world wars that road trips could be a profit machine made a fortune. And their grandkids’ grandkids are still cashing in every time my Apple Pay clears and the odometer resets the countdown to another 450 miles. Reese’s Pieces, a biscuit, and iced coffee from some beaver store nestled into the center console. I sank back into the seat, floored it off the ramp to avoid being stuck with more semi-trucks, and the hours returned to a blur—steering, merging, and occasionally telling assholes who cut off people to go fuck themselves.

Two days later, the Outer Banks were beneath my wheels. Recounting the other family trips where I’d had less income, independence, and camera gear flickered in my head as key recurring scenes passed by. This wasn’t the first beach I ever knew, but it became pilgrimage ground—first for my parents, then just my father, and by proxy, all of us siblings when we could gather alongside him. Each return marked a new chapter of the creative life inside me. Every age being one that got marked by major milestones. The self-doubting, green, and uncertain photographer I used to be once thought that magic was at this place. The kind my grandfather’s old family beach trip albums had in them. This island where everything stayed the same like He did.

I scribbled pieces about this into a worn-out journal while port guards walked past lines of idling cars waiting for the inbound charter to Ocracoke. My Leica sat on top of the camera bag in the passenger seat, chrome body flashing when the clouds shifted. The legendary Leica M6 and dozens of unopened rolls of film rested beneath it. That camera was the last present my parents gave me together, before they split. A relic of when the circle was still two ends of a line conjoined. My pen scratched against damp pages until the ink thinned out. By dinner, I’d need more pens. Realizing these things was interrupted by the ferry opening its jaws. Crews ushered cars, vans, and trucks into columns. Brakes squealed. Lights flashed. Rain began to collect heavily on the deck as the water lapped white against the hull. Hydraulic yawns from the engine rooms clashed with the screams of gulls. A thumbs-up confirmed the parking brakes were locked, and just like that, the voyage began.

Every state in the union was left behind for the tiniest grain of land: A village East of where East begins.

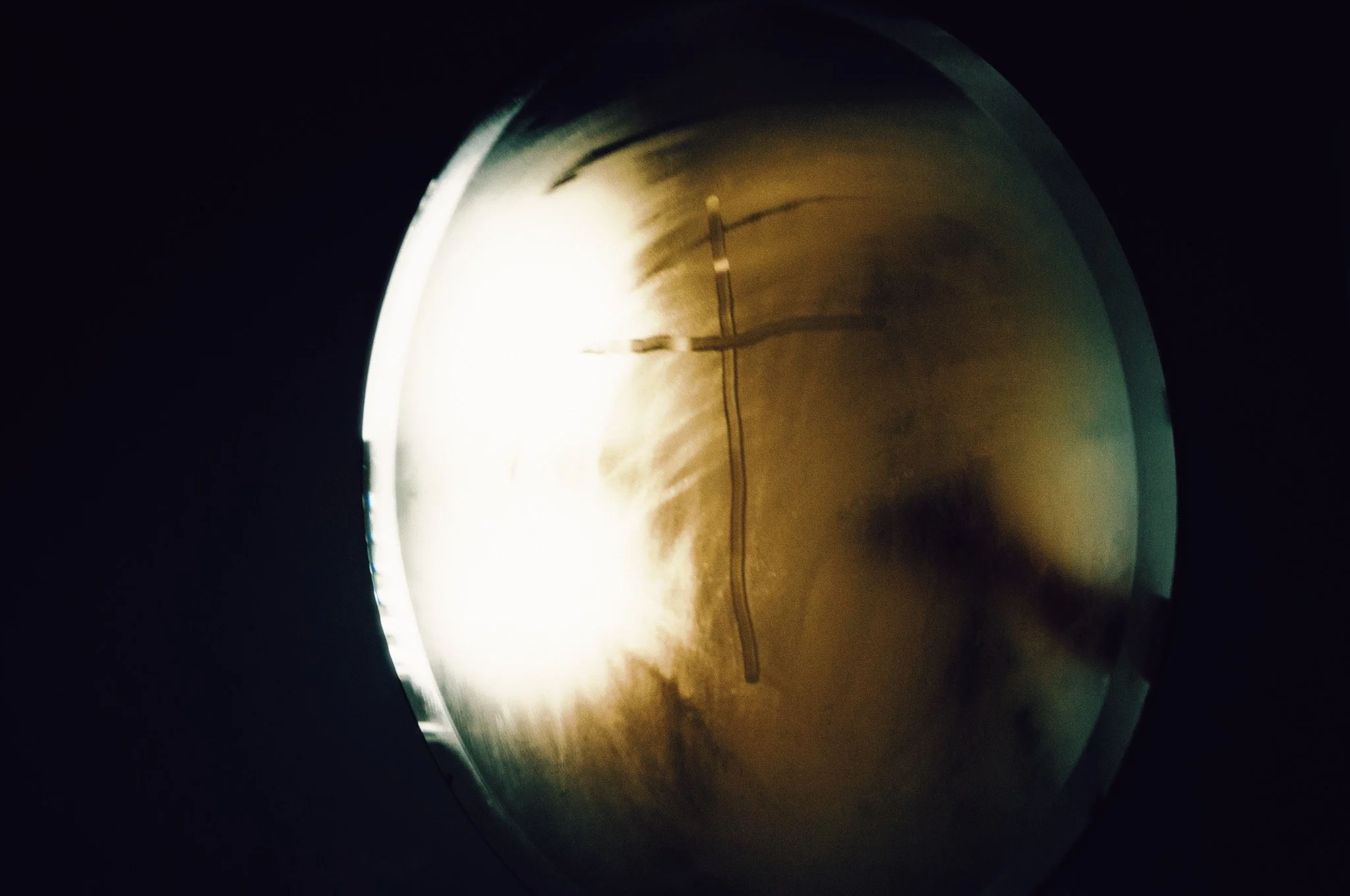

I squeezed my linebacker shoulders through narrow rows of vehicles, camera ready, lungs open. The ferry is bare for what it carries. Wide enough to feel endless, stripped enough to humble you. No free alcohol. No stewardesses grinning as they drop another bag of pretzels in your lap. Just the hum of engines and the possibility of sea air. My legs already knew how to find the stairs and climb upward toward the passenger seating area encased with bay windows on every side. In the lounge, my camera drew glances. I raised my hands, joked I wasn’t about to shove a trash-can-sized lens in anyone’s face and call it art. They chuckled. The tension broke, and all my cards were in the open. Intentions were accepted. The passengers were just like me—bored, restless, already wishing for sunburn and aloe to soothe it. The chairs in the lounge are the coldest shade of warm leather. It mixed directly with other purposeful decor, such as tide posters, portraits of government officials, and the green uniforms of staff attempting to get thirty minutes of TikTok in peace. I’d remembered this place many times. One of my earliest portraits that I loved of my sister and mother was shot through these same windows. The condensation and the light made a remarkable painterly scene. Intuition goaded me toward that feeling. So I leaned in.

My ass found the exact chair that was used so many years prior, and my eyes drifted past the glass and railings to the infinite horizon beyond. And the moment I sat, it was there again. That same splinter of light. The same cut across the glass that had framed my sister years ago, back when the family still moved as one body. The chair itself became a trigger, pulling me straight through the years without my permission. Light doesn’t ask permission when it folds time. It dragged me back the instant I touched that seat, collapsing years into a single breath. Lashes on the roof and floor of my eyelids were motionless as the horizon began to glow. My body froze and past the water drops and windows and passengers taking selfies, was a return. The same eggshell of cumulonimbus from a decade before started to bleed out the mixed grays and drizzles of rain. Tiffany blue skies peeked behind it all, and recollections of my sister’s hair bouncing as she laughed with my mom and walked past the seat tinged my fingertips with a bit of cold. The blood finding its way to the core of my chest as a smile formed. I could feel the same joy again from making that picture. Shock and amazement and everything wonderful.

Then a door slammed. Gulls screeched again, and a breeze covered me while a family struggled to keep the door from hitting the wall again. Crowds started to thin as the island became larger than the stretch of water we were on, and staff were telling folks it was time to get back to our vehicles. Minutes later, a chorus of engines igniting was greeted by the drawbridge lowering onto our ferry’s bow, giving a clear path to grit, sandy pavement, and a thin two-lane highway directed every bit of traffic toward the village.

I unloaded what I could for the rest of the family and went to find the cottage where my aunt and uncle were staying. It was only a few brief turns from the local cafe that could pass as Central Perk if it weren’t built with bricks or in New York or set in the 90s. Within a stone’s throw of that lovely watering hole was the spot I ran my first 5K and threw up from the rookie mistake of accepting water at the halfway mark. Puddles rippled with tourist bikes, and there were more pedestrians than vehicles in both lanes. Underneath a grove of gnarled trees, thin pebbled gravel invited me off the main drag and toward the cottage. Deckboards and furniture stretched far into every direction of the yard. Once the keycode was entered correctly, the clicks retracted the seatbelt, and I turned the handle to enter something straight out of a nineties film. Think Dillard’s catalog in the Hamptons with less emphasis on denim and more on the often odd color combination of vegetables that form a base of pico de gallo. Martha would’ve had this place whipped together with some type of collab. Maybe a soft launch for Zondervan’s next take on the KJV, or a capsule collection with JoAnn Fabrics. Maybe both. At this point, a calm covered the room. Fans creaked with gentle swinging motions throughout the house. Faint diffusing cloud cover made the rooms gently brighten and fall again into shade. The camera battery spares were charging, so after unwrapping the bedsheets and getting things situated, I crashed on the sofa, finding immense satisfaction in the restful experience. Instagram notifications on my phone were going off, but I ignored them. For one of the only pieces of this trip, the cottage was entirely for me, and nobody could do anything to change that.

Hours later the family convened at the local pub. In typical fashion I was early and made small talk at the front welcome station as the staff told me to take whatever photos of the room I’d like. Across the rafters and into every corner of the ceiling, license plates and oddities were nailed into boards like a collage of other family passages. The Griswolds were up there someplace no doubt. My fresh shirt was fighting the humidity, and waitresses wore the smiles of tourist season as they sloshed pitchers of ice water around the table. It only took a few minutes for the first beer to land. Not much of a beer guy anymore, but you don’t note that to the table when you’re doing this sort of gathering. Quickly after the first round, a second arrived followed by a mess of fried things nobody pretended were healthy. Conversation climbed quickly. The chatter was easy, familiar, and the walls of the last several months began to loosen.

My dad’s laugh cut through it. Not booming, not theatrical. Just the sound of a man who made it to fifty-five and still had something left in the tank. Being a new grandfather looked good on him. He wasn’t in his late twenties anymore, but neither was I. And our connection was clear. Laughter rose from the rest of the table. Jokes turned into inside jokes. Bacon was added to many entrees. The hum of other tables blended into our own, and for an hour it felt like nothing in the world could demand more of us than this. Collectively, there was a softness. A decompression beginning like how the leaves turn every fall. Work and life had eaten their fill of us, drained what they could. But this table was the first rebellion against that routine. A first-fruits offering to whatever part of God’s character decided that day seven was meant for rest long before anyone built spreadsheets or 401(k)s. And the colors were changing for the better.

After dessert and paying the tab, folks disinterested in sending it to the sandy shore allowed us to take a single truck. My old man had already cleared the bed of his Duramax out and had the rods bundled for safekeeping to the beach access. Seats were open in the cab, and A/C was flowing, but some part of myself didn’t want that. Sitting in the bed of the truck and shooting along the way felt much more true. Why true? Don’t ask me. It just did. Little things aren’t little if your gut is kicking your ass to do them, so I followed its beckon.

There was enough of a buzz still left in me from the pub to know that my photographs were going to be good. Alcohol can’t predict the future, but it definitely gave some hints. I dabbled some sentences about this in the notes app, just as a sharp left turn slid my shoulders against the rear windshield. Looking above, we were losing the day. It was going to be tight. Shortly after passing by the pub, we turned off the byway and entered the brush of the grasslands dividing town from the coast. The rain had intensified many potholes along the beach route, so instead of whomping again and again against the glass, my legs pushed me high and straight upwards to see clearly and around. The orange of these past few mornings found its twin in the afternoon golden hour. Egrets motioned through the grass like angels, and I laughed. That’s a good sign. The reaction became involuntary a few years ago. Not sure why, but it became commonplace when cameras and writing were made paramount priorities over attempting other recreational dopamine triggers like cocaine or serial dating. The closest definition of this phenomenon is being high on life. Which sounds like something you’d hear at a youth group retreat, or written for a Seth Rogen ad, but it hits different when you’re standing in the bed of a diesel truck aimed at the Atlantic. Because despite the weight of everything—every mile driven, every job, every obligation—my lungs still pull air. My eyes still register colors. My hands still know to lift a camera in response. The weight of living is something all of us feel, and when you document this so that other people will one day get to hang it on a wall, it overwhelms the split and paradoxical intensity of a modern American artist. The shadows and the highlights of this experience are too hard to ignore in a burning world, but if I’m being honest, is there any better way to be? After millennia of trees dying to make paper and billions of 2-for-5 lunch combos going out the door annually, it begs the question of how much of this fragile system can handle my freedom. My endurance to drive nonstop to once again be someplace that resonates with my migratory family patterns is unshakable to what I am, and maybe the key to that isn’t avoidance but the recognition of something deeper

The great pendulum swing of these questions haunts me like an old man and my inner child fighting over the dinner table. I picture them clearly sometimes—the child restless, the old man bitter, both of them looking at me to choose sides, and me chiming in that the only thing that matters is how much this will still be here when I have a kid of my own. A little shutterbug who talks about getting their passport at age nine and already knows how to load a roll in the same camera my parents gave me. The same camera I hold on to like an heirloom of a different life. Everything we think isn’t always true, but everything true can be something we think. And in that moment, riding the bed of a truck with salt in the air and angels in the marsh, I knew this was one of those truths. Every ounce of this should be saved for as long as it can. It deserves to be witnessed for generations onward.

Another pothole shaking my body and the fishing rods pulls reality back into frame. Just in time for the light to reach us near a receding tide, with tire tracks crossing and recrossing the sand like a legendless map. Shells scattered everywhere, roars from the Atlantic were uncontainable. Clouds billowed, purples started rising to dominate the last gold of the mist miles above our heads. Blue hour was knocking at the door. For a split second I noticed a plane high above the seagulls in my camera’s frame lines: maybe flying would’ve been better for this moment. To see it all from above. But the thought shook off as whispers of night flicked against my skin, with tiny sheets of sand collecting on the hairs on my legs. Everyone drifted toward the water with rods in hand. I caught a few pictures of the tackle and the bait, then sat on top of the truck cab, pondering.

Whatever photographic lessons live here fall squarely into the category of things you only learn by time in the saddle. By not being young anymore, but also many years off from being old. By shedding one shell only to grow into another. Somewhere in the middle of everything, a fact of life insists that we are who we are until we aren’t, and even that feels like a cosmic joke. But pilgrimages to an island—this rare, fleeting, convergence of light and family—is the closest thing to heaven we may document in this dimension. And when you don’t just participate in the memories, but preserve them, you see smiles and love in the eyes of people you never want to lose, fully aware your prints and files and film negatives will have to suffice once they’re gone. It makes the return everything. Knowing that on the other side of all of this is something more than our imaginations can prepare us to fathom. So when the questions come in the middle of radiant and bursting colors of wonder, I raise my Leicas and continue until the only light left is a sea of jewels high and far above the clouds. I relive the intent and passion of my step-grandad with his Minolta, sitting in a beach chair as the sea foam swallowed his feet. And the love of my father, who’s still here, walking the waves with a rod, indifferent to a world of convenience, and certain about the healing powers of returning to this island whenever we can. Every frame and click of mind adds to their lore.

My handwritten notes back in the cottage that night spoke about how every shutter click and film advance shakes us alive fractionally. That in the continuance of this magical energy, there’s a love you can feel in everything if you want to believe it. Reviewing the photographs the following morning confirmed this. Confirmed who and what I am to those who matter. Because in family traditions like this cross cross-country sprint from the Midwest to the coast, we become one with the endurance that drives us to this place, again and again and again. It’s a masterpiece in plain sight. A symphony of meaning. And as long as the legs can carry me here with them, I’ll be present to see it. As will so many more of us. Until there’s nothing East of East to stand on anymore.